Report: Eight nights in Italy

With the help of a Gerry Grimstone Travel Award, History undergraduate Rob Lentz was able to take an eight-night trip to several major Italian cities, for the purposes of cultural and historical development; he flew to Venice, then caught trains across the Italian countryside to visit Florence and Rome before returning home.

Venice

My original aim when visiting Venice, had been to develop my understanding of the city’s role in the Fourth Crusade, an event which I had studied in the Hilary term of my second year. I’m very pleased to report that not only was I able to achieve this, but much more as well.

As far as my Crusade-based purpose is concerned, I did not have to look far to get a sense of the importance of the Fourth Crusade to this Italian trading city: seeing the horses atop the West front of St Mark’s Basilica, taken from the ransacked city of Constantinople following Doge Dandolo’s victory over the Byzantine capital in the early thirteenth century, was an emphatic statement of the role that the eastern-bound venture has had in shaping the identity of the city.

Additionally, I was able to further develop my understanding of how the lagoon province of Venetia functioned as a commercial network of interrelated islands, by embarking on a tour of the islands which surround the main island. In particular, visits to the Islands of Murano and Burano gave me the opportunity to witness, first-hand, artisan trades in practice that had characterised these islands for centuries: glasswork and lace embroidery, respectively. Before this visit, I had no such concept of the multitude of trades which Venice was a leading market for, presuming it to be entirely dominated by import trade activity.

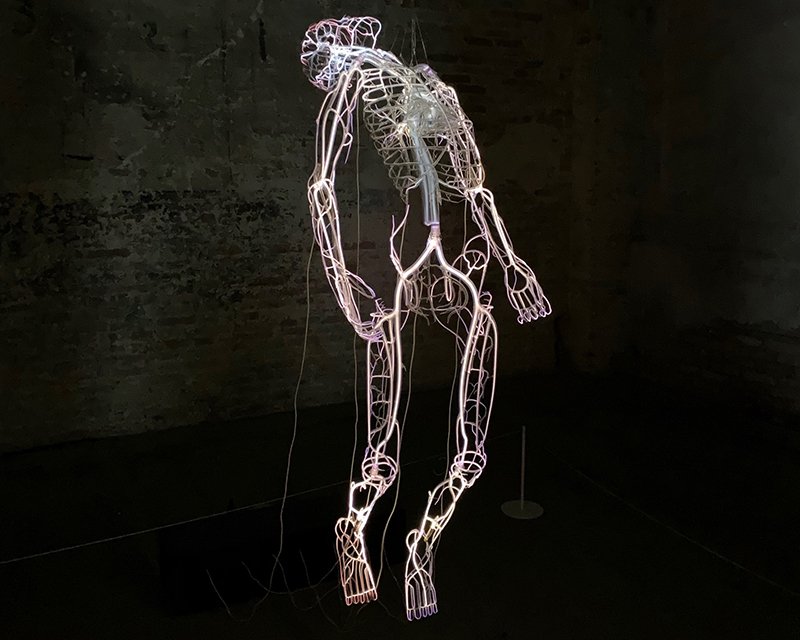

The most striking, and in my opinion, memorable, aspect of my time in Venice, was something which I had not anticipated at all: the Biennale. Stumbling across this bi-annual exhibition of modern art in the Arsenale, which I had originally gone to in order to learn more about ship manufacture, was a most pleasant surprise. As someone who would not usually take oneself to a gallery exhibiting ‘modern’ art, I found the international exhibition immensely enjoyable, and quite eye-opening in terms of my artistic preferences. The diversity of the pieces on display, and their sheer number, was something of a baptism by fire into a genre of art which I look forward to developing my knowledge of more, as time goes on.

I had expected my main cultural takeaway from Venice to be the exposure it would give me to Palladio’s architecture, something of great relevance to the module on English Baroque Architecture that I am studying this Michaelmas term; instead, it was the vast collection of modern works of art that the Biennale gave me access to.

Florence

When I applied for the Gerry Grimstone travel grant, I had been intending to write my thesis on fortification developments in Early-Modern Europe; as such, I was keen to visit Florence, in order to see the canonical examples of trace italienne walls that are so well-preserved at the Forte di Belvedere, and also several miles outside of the city. However, by the time I came to arrive in Florence, my thesis subject had changed quite substantially. As such, I instead used my time in Florence to immerse myself as best I could in the artistic culture of a city so central to the Italian Renaissance movement.

Being surrounded by Florence’s architecture was very useful for consolidating my understanding of the use of classical features of architecture in the Baroque, and for developing an appreciation of the ways in which 17th-century English architects such as Roger Pratt and John Evelyn may have been influenced by their travels in Italy. I include here an image of a front which I found particularly interesting, just beside the Palazzo Vecchio. Pairs of Corinthian pilasters stand below a curved pediment – thus far, nothing unusual in the canon of Baroque architecture – but the inverted and broken circular half-pediments which crown the building are most unusual, and continue to hold my interest. This is a single example, but one which hopefully gives an indication of the value and excitement which spending time in one of the heartlands of Renaissance architecture brought to me.

Being in Florence meant that, at long last, I was able to visit the Uffizi. Having studied the art movements of early modern Europe at length in the first year of my BA History degree, being able to finally see such hugely influential works as the Botticelli triptych, Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck, and Titian’s Venus of Urbino, in the flesh, was an incredible experience. I was grateful to have already studied these pieces before having the chance to see them, as it added so much to the long-overdue experience of doing so. Furthermore, the transition from a very contemporary collection of works of art in the Biennale, to so excellent a gathering of works all dating from before the nineteenth century, meant that this trip had already covered a fantastic breadth of artistic genres and periods.

One of the great joys of my visit to Florence was simply walking around the city – so much of its centre is so well-preserved from its heyday under the Medici family, that one feels almost transported back to their time. Architectural quirks like those discussed above abound – indeed, the hotel I was staying in was opposite the Palazzo Pitti, a unique example of the extreme use of rustication on a façade. Finally, the duomo – the first dome of its kind since the fall of the Roman Empire; was genuinely rather awe-inspiring to see in person. Now that I am studying the work of Sir Christopher Wren and his peers, I am inclined to wonder how far knowledge of Italianate basilica domes inspired or influenced the work of England’s own baroque architects.

Rome

I concluded my trip to Italy by spending three nights in Rome. Here, I was able to walk in the footsteps of mid-seventeenth century English architectural theorists such as Roger Pratt and John Evelyn, visiting the ancient sites of the Pantheon and the Roman Forum to appreciate these examples of the classical orders which would have so greatly influenced Italian Renaissance architects. Whilst wet weather impeded my ability to explore the city much upon first arrival, the next few days gave me the opportunity for some valuable experience of Rome’s delights.

Standing under the vast portico of the Pantheon gave me a newfound appreciation for the cultural legacy of the Roman Empire, and also an immersion in archetypal Corinthian columns. Also, it provoked questions of how far the domes employed by English architects of the 1660-1720 period – which I am currently studying – used the Pantheon as a reference for the structural requirements of domes on buildings. A trip to the Piazza del Popolo, originally the Northernmost piazza of the city, gave me an opportunity to see the effectiveness of the city’s plan: the three sight-line vistas which extend from this piazza produce a most striking effect, and perhaps the inspiration for Sir Christopher Wren’s plan for the City of London following the Great Fire of 1666.

Furthermore, a trip to the Colosseum was of great use from the perspective of my interest and studies in classical architecture: it is one of the few preserved Roman buildings where one may find example of four of the five classical orders, and also an indication of how Romans navigated issues of proportion and arches.

Conclusion

My trip to Italy over the long vacation provided me with far more exposure to artistic culture than I could have anticipated. Furthermore, to observe first-hand works of architecture by those Italian figures who would become so influential on English architecture from the time of Inigo Jones onwards, was of significant benefit to my studies of English Architecture between 1660 and 1720. I am very grateful to Sir Gerry Grimstone for his kind benefaction of myself, and other Mertonians.