Report: A Cathedral Adventure

During August 2021, Physics undergraduate student Alex Pett travelled to five Gothic cathedrals around England in order to study their history and architecture and write about his experiences.

I undertook this journey because I am fascinated by Gothic cathedrals. I am fascinated by them because they are so ancient, so intricately decorated with stunning stone and glasswork, and so rich with history and religious symbolism. I used my Gerry Grimstone travel grant to learn more about these medieval monuments to the divine.

The first cathedral to which I travelled was that of Worcester. I had never been to study a cathedral in person before and I did not know what to expect nor at what to look. What I found in Worcester was an overwhelming abundance of information and beauty. Scenes from Genesis were carved into the stone above the West door; the pulpit was crafted from luminous marbles of milky white, pale red, and green; the font stretched metres high with pinnacles and spires; and the tombs of King John and Prince Arthur adorned the presbytery. There was simply too much information for me to take in and write about. Thus, for my subsequent trips, I had to choose a particular aspect of cathedrals on which to focus. I chose their architecture because I wanted to be able to label the things at which I was looking and because any part of each cathedral’s history would almost certainly be intertwined with its architecture.

On the morning of 24 August 2021, I took the train to Durham. Durham cathedral, the building of which started in 1093, is most notable for its dominant position. It is strategically located on the top of a peninsula and, from there, it towers over the rest of the city below. This intimidating feeling does not diminish once inside the cathedral. This is because the nave of Durham cathedral is an exemplar of Norman architecture. It contains huge columns, deeply incised with decoration, as well as fierce chevron mouldings engraved in its semi-circular arches. These are all distinctly Norman architectural features and they do well to convey the message of power and dominance that the new conquerors of England wanted to send.

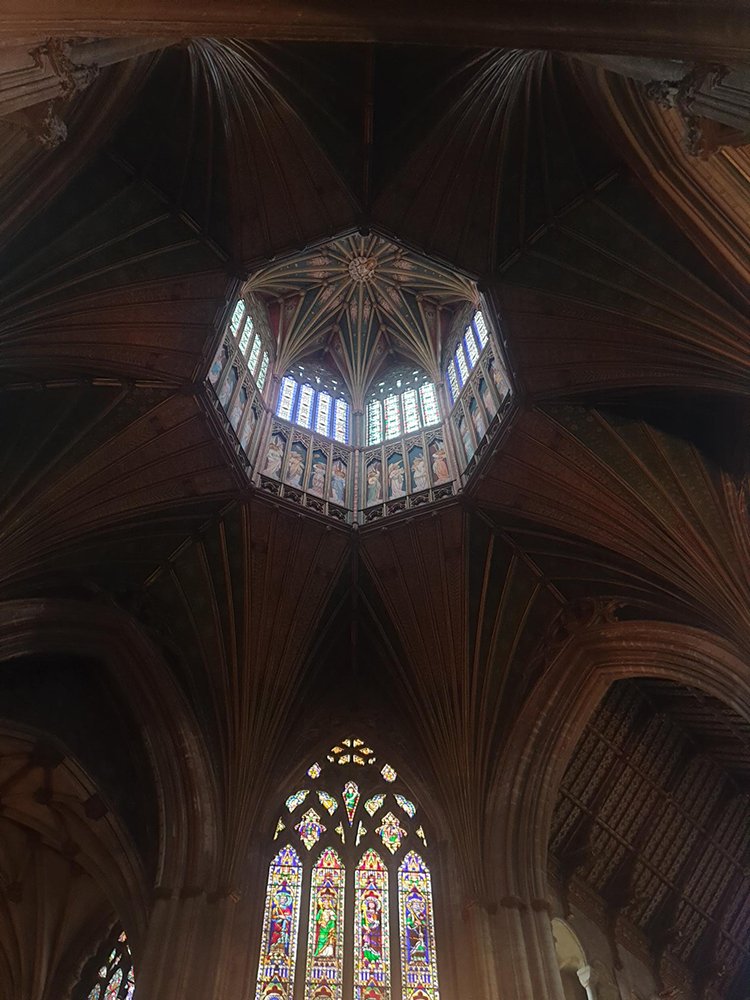

The city of Ely was my next stop, for 26 and 27 August. The cathedral of Ely, which dates to 1083, is most famous for its octagon. This is an eight-sided stone structure at the centre of the cathedral (where the nave meets the transept) which is topped with an octagonal lantern which illuminates the cathedral like no other. It is one of the crowning achievements of the Decorated Gothic period (1250-1350) and is adorned with the characteristic elements of the style – ballflower crockets, ogee arches, and mouchettes flowing through its window tracery. Yet the most wonderful thing about the octagon is its history. It is the result of an awful tragedy. In 1322, the Norman tower of Ely cathedral collapsed and the head monk, Alan de Walsingham, fled the scene. However, he later returned and decided to seize the opportunity lying within this moment of distress by building this unique architectural feature that still dazzles onlookers today!

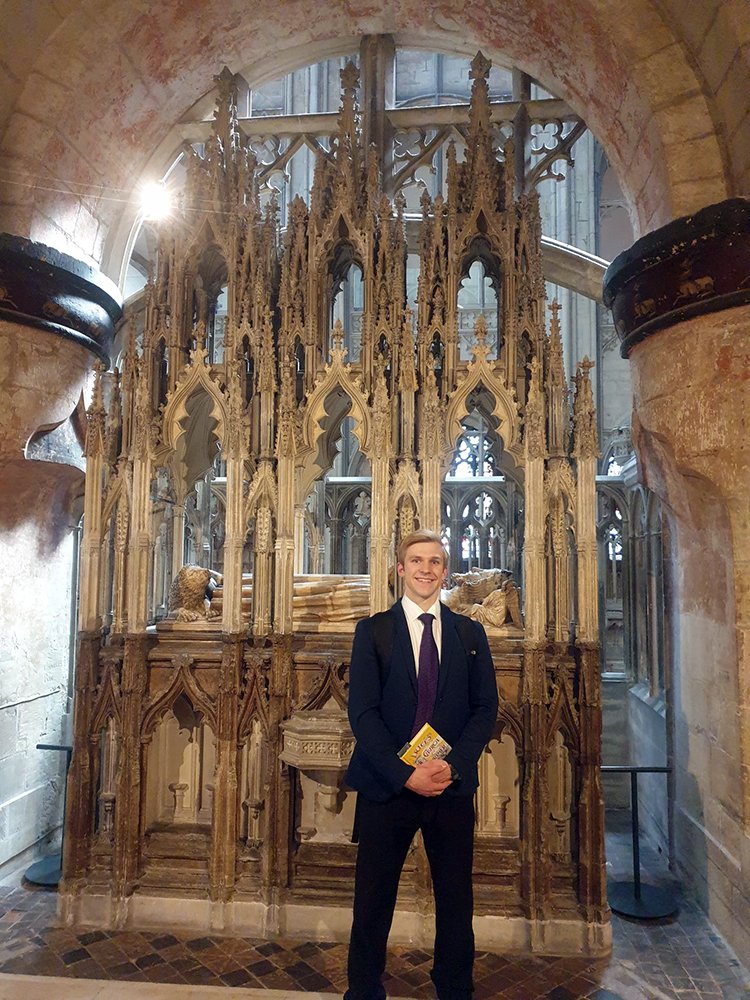

The penultimate city to which I made my cathedral pilgrimage was Gloucester. Gloucester cathedral, the building of which started in 1089, is home to the tomb of Edward II. Edward was an unpopular king and was murdered by his wife and her lover in the nearby Berkeley castle. Despite his unpopularity during his life Edward III, his son, was able to transform his father’s reputation by building a great tomb to Edward II within Gloucester cathedral. This tomb is another fine work of the Decorated Gothic period and it is richly adorned with sinuous ogival arches, crockets and spires, which form a canopy over the moving effigy of Edward II – one of the first known uses of alabaster in sculpture. This tomb brought pilgrims and further patronage to the cathedral, leading to the ‘reclothing’ of its East end in the new Perpendicular architectural style. One story goes that the local parishioners were against the demolition of any part of their church, and so the architects were forced to overlay and thus encase the original Norman walls in the new Perpendicular style of panelling.

My cathedral adventure came to an end in the city of Wells – England’s smallest city! Unlike Durham and Ely, whose cathedrals are visible miles away, I turned a corner and found myself unexpectedly faced with the great Western façade of Wells cathedral (the building of the cathedral started in 1176). It stopped me in my tracks. The West front of Wells is an exemplar of the Early English Gothic style of architecture – each of its myriad niches are decorated with delicate en-delit columns (columns which are not directly attached to the wall behind) and topped with stiff leaf foliage, both diagnostic of the Early English period (1170-1250). The effect, for me, of the replication of this intricate detail across such a vast façade was that I was overwhelmed by the sight when I first stumbled upon it. Within Wells lies yet more beauty. Three ‘scissor arches’ are found in the crossing tower of the cathedral. These were so unlike any other Gothic architectural feature I had come across that I initially thought they were modern installations – pretty, but recent decorative additions. I was wrong – the scissor arches date back nearly 700 years and are structurally integral to the cathedral! In fact, they were installed to brace the cathedral tower after cracks had begun to appear in its columns. In the 700 years since, not a single crack has been sighted.

These scissor arches at Wells, alongside the octagon at Ely, arose out of distressing situations. It was the cracking of the crossing columns which inspired the scissor arches at Wells and it was out of the collapse of the crossing tower at Ely that the octagon was conceived and constructed. They both illustrate to me the most poignant lesson of my cathedral adventure: great beauty and opportunity lie in even the most distressing of situations.

I am thankful to Lord Gerry Grimstone for his generous travel grant and the cathedral adventure that it enabled me to undertake.