An Unexpected Discovery: Early Modern Recycling

In 2016 Professor Artur Ekert generously gave the Library a donation to conserve a beautiful 17th-century natural history volume by John Jonston. The book caught the attention of the College’s head conservator Jane Eagan (Oxford Conservation Consortium), thanks to an unusual stamp on the inside board of the binding. This turned out to be a trade stamp from a ream wrapper (used to keep reams of paper together) which had been reused by the binder – a rare find. Jane explores the provenance of the wrapper.

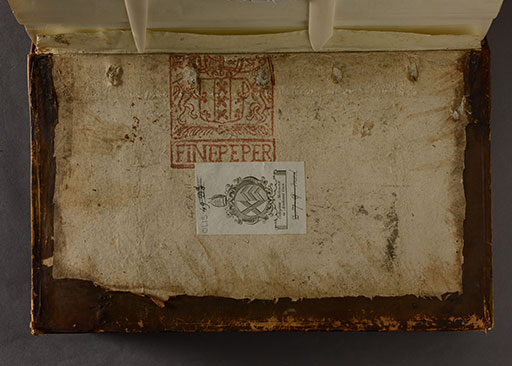

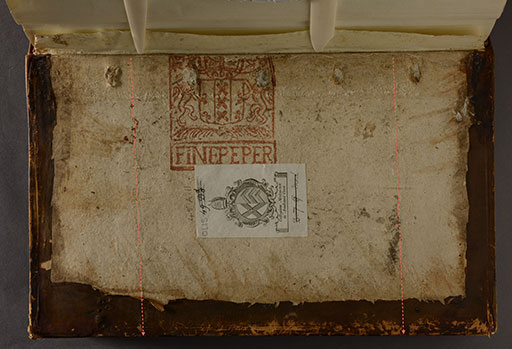

Discoveries still happen in day-to-day Special Collections work. I was recently asked by Fellow Librarian Dr Julia Walworth to look at the damaged text-block of Merton’s copy of John Jonston’s (Joannes Jonstonus) Historiae naturalis quadrupedibus libri (1657 imprint, Ioannem Iacobi). This beautifully printed natural history volume is in a plain workaday late 17th- or early 18th-century English binding, and the title page had been damaged with unsympathetic earlier repairs. As I started to examine the volume, it was an unusual detail on the facing page – the inner face of the upper binding board – that caught my eye. The board had been made using recycled paper which was woodblock printed, identifying it as a reused ream wrapper – a rare find.

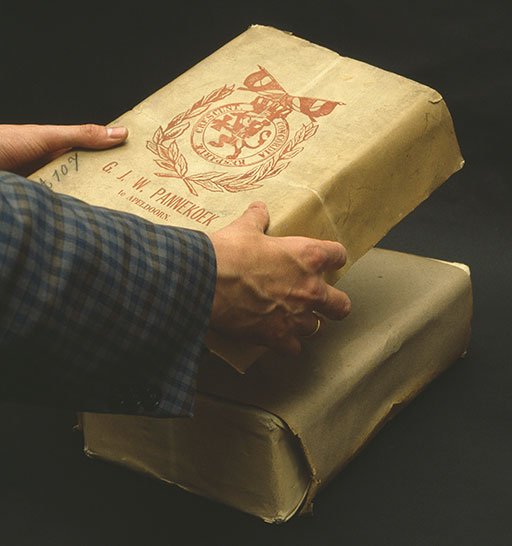

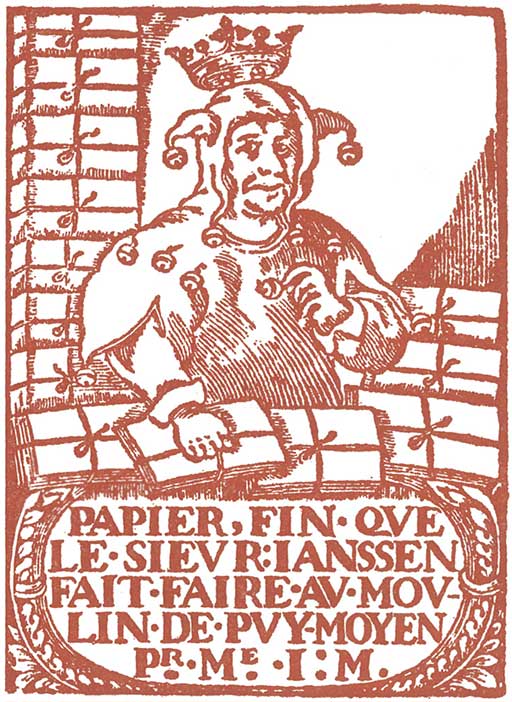

Ream wrappers were produced by paper makers and were wrapped and tied around each parcel of 20 quires of paper—a ream—to protect the paper during transport. The printed design on the wrapper identified the quality of paper, and sometimes the papermaker, and was often the same or similar to the watermark of the paper it contained (as in the case of the Moulin du Verger’s fool). In Holland and France ream wrappers were commonly made of coarse thick paper or thin board, called 'maculature' in French (defined as 'papier grossier servant à emballer les papiers en rames'). This thick paper was made of cheap reused materials such as coloured rags, woollens, discarded paper, trimmings, etc., and was rather bulky and soft with poorly-beaten material still visible in the sheet. French, Dutch and Swiss ream wrappers were often printed in red ink.

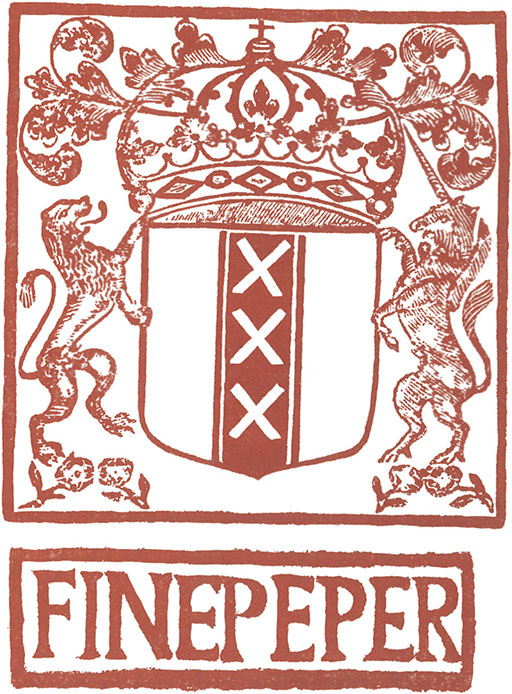

The ream wrapper in Merton’s volume was partially obscured by an internal hinge of paper along the inner joint, put in when the volume was rebacked by local Oxford bookbinders Maltby's in the 1960s. When I lifted this hinge, the two supporters on either side of the shield were revealed: two lions, the symbols of Amsterdam, with the odd legend FINEPEPER below. This echoes another, very similar, ream wrapper reproduced in Henk Voorn’s Old Ream Wrappers (North Hills, PA: Bird & Bull Press, 1969), on page 61. Voorn’s wrapper comes from his own collection and he dates it to 1697. The design of his example depicts the arms of Amsterdam with the central shield supported by a lion and unicorn, symbols of England and Scotland. Below this appears the words FINEPEPER, which Voorn theorises is the phonetic spelling of FINE PAPER by a French or Dutch woodcut artist unfamiliar with the English language.

Merton’s ream wrapper is printed on a thin (c. 0.3mm) sheet of greyish pulpboard, with many inclusions and a relatively rough surface. This board has been laminated to another, thicker, layer of pulpboard to provide a more rigid board for the volume. Two folds – one about 3cm from the left edge of the printing and the other about 10cm away, to the right of the printing – can be seen in the pulpboard. The wrapper would have been folded around the ream of paper with the printed label at the top, creating these two fold lines. These folds allow us to determine the size of the paper contained in the ream. They show that the wrapper contained a parcel about 224mm wide, with the printed design on the upper surface. On the upper right edge of the printed design, there is a mark left by a string or thin cord which seems to have been dipped in red ink or paint. This is slightly redder than the ink of the wrapper label which is more orange/brown. Could this have been the cord used to tie up the ream of paper? As the quires were folded in half parallel to the short side of the sheet of paper, this gives a sheet size of 448mm in the longest dimension, or about 17½ inches. The nearest paper size to this is foolscap writing paper at 13¼ by 16½ inches. It is likely that this is an example of a printed ream wrapper for a bundle of French or Dutch foolscap fine quality writing paper destined for the English market.

The lower book board is also made of a thin board laminated to a thicker board, and is most likely another waste ream wrapper, although no printing or discernable fold lines can be seen on the exposed surface. It may be that the ream wrapper used for the lower book board has had its printed surface laminated to the second, thicker board, leaving the unprinted side face up.

Merton’s copy of Historiae naturalis quadrupedibus libri was probably bound locally in Oxford. Given the rarity of ream wrappers, it is interesting that this one shares an Oxford connection with another ream wrapper in the rare books collection at Princeton: Miscellany Poems and Translations by Oxford Hands, printed in London in 1685 for the Oxford bookseller Anthony Stephens, and with the ex libris of William Preston, Queen’s Oxon, 1742 on the upper flyleaf.