Benefactors

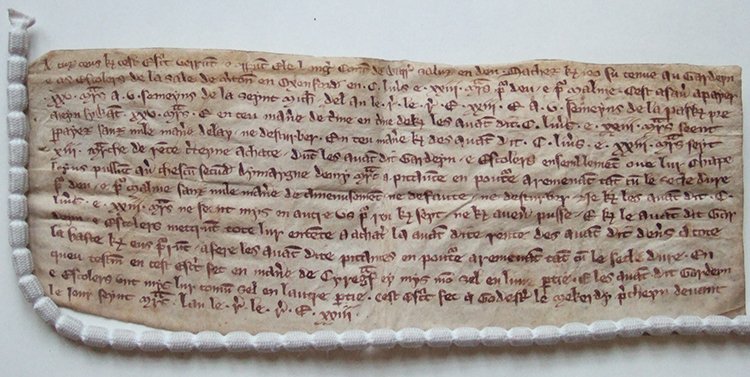

Ela, Countess of Warwick, was the College’s first great female benefactor and her life shows us the varieties of influence open to some aristocratic women in the age of Walter de Merton.

Ela’s ancestry was royal, being descended from King Henry II by a noble mistress, Ida de Tosny. Her father, William Longespée, had married Ela Fitzpatrick, heiress to the earl of Salisbury. One of eight children, Ela and her three sisters all made aristocratic marriages.

Ela’s first husband was Thomas de Newburgh, earl of Warwick and on his death without children in 1242, Ela kept one-third of his lands. A dozen years later she married Philip Basset, a man close to the centre of power and a versatile servant to King Henry III.

Photography by John Gibbons

Between 1261 and 1263, Walter de Merton and Philip Bassett between them led the king’s administration as chancellor and justiciar respectively. In November 1266, Philip and Ela made a major donation to further Walter’s educational project. They granted the manor of Thorncroft in Leatherhead, Surrey, to Walter for his life and his ‘house of scholars of Merton’ after his death. In 1268 he handed it over to the College and it still remains in the College’s hands.

Philip Basset’s death in 1271 left Ela with yet more land and, as she did not marry again, considerable freedom of action. She gave lands to St Sepulchre’s Priory, Warwick, for example, to pray for the souls of her late husband the earl of Warwick, her mother, father and siblings. Her grant to Reading Abbey in 1282 provided for a special distribution of spices to the monks and extra food on Thursdays and Sundays.

Ela spent her later years at Godstow Abbey, just outside Oxford, although as a vowess rather than a fully professed nun. Kings Henry I and Stephen had been involved in the foundation of Godstow and its nuns were often from aristocratic families, so Ela probably felt at home in their company. But another attraction must have been its proximity to the College and the University, with which she was enthusiastically engaged.

She gave money to Balliol for the building of its chapel and established a fund from which the University could make loans to poor students. But her links with Merton were particularly warm. She wrote heartfelt letters to the Warden in French, as befitted an Anglo-French noblewoman, addressing him as her dear special father in God, asking for his help and advice and pledging that making gifts to the College was one of the things she most desired on earth.

Ela died on 12 February 1298 and was buried at Godstow. From then on, the fellows must have remembered her every second Sunday, as they enjoyed the drinks that she had endowed for them, and especially on St Matthias’ day, 24 February, as they prayed for her soul and enjoyed the additional drinks that she had provided in another of her benefactions.

Margaret Dane, née Kempe, was the daughter of a wealthy mercer (dealer in fine fabrics) of the City of London, and granddaughter of Sir Thomas Kempe, three times Sheriff of Kent. In 1542 she had married William Dane, a native of Bishop’s Stortford, whose father had sent him, like Dick Whittington, to London to make his fortune. He had been apprenticed to an ironmonger, and was subsequently elected a liveryman of the Ironmongers’ Company in 1559. Notwithstanding his original profession, he transferred his activities to the trading of fine textiles like his father-in-law, and became one of the wealthiest men in the City of London, serving as Sheriff of London in 1569. At his death in 1573 he left instructions for bequests to a number of charitable institutions, like St. Bartholomew’s and St. Thomas’s Hospitals in London, as well as to the founding of a grammar school in his home town.

Image: Reproduced by permission of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, London.

Margaret Dane was clearly an able business woman in her own right and continued her husband’s trading activities for the next six years. Among other customers, she supplied linen to the royal household and at her death in 1579 was wealthy enough to leave a gold necklace worth £200 to Queen Elizabeth I. It is uncertain that all her husband’s charitable bequests had been put into effect, but she herself left £2,000 in trust to the Ironmongers’ Company, the annual interest from which was to be applied to various charitable purposes in both London and Bishop’s Stortford. These included loans to set young tradesmen up in business, the annual distribution of food to prisoners in the main prisons in London, Southwark and Westminster, as well as the distribution of fuel to the city’s poorest inhabitants. In addition, she established two academic Exhibitions each to the value of £5, one each at Oxford and Cambridge, for the maintenance of poor scholars. The Oxford exhibition was established at Merton College, which may have been selected because of historic links with the Kempe family. John Kempe, archbishop of Canterbury 1452-4, had been a fellow of Merton c.1395-1407, and Thomas Kempe, bishop of London 1448-89, had also made a significant bequest to the college.

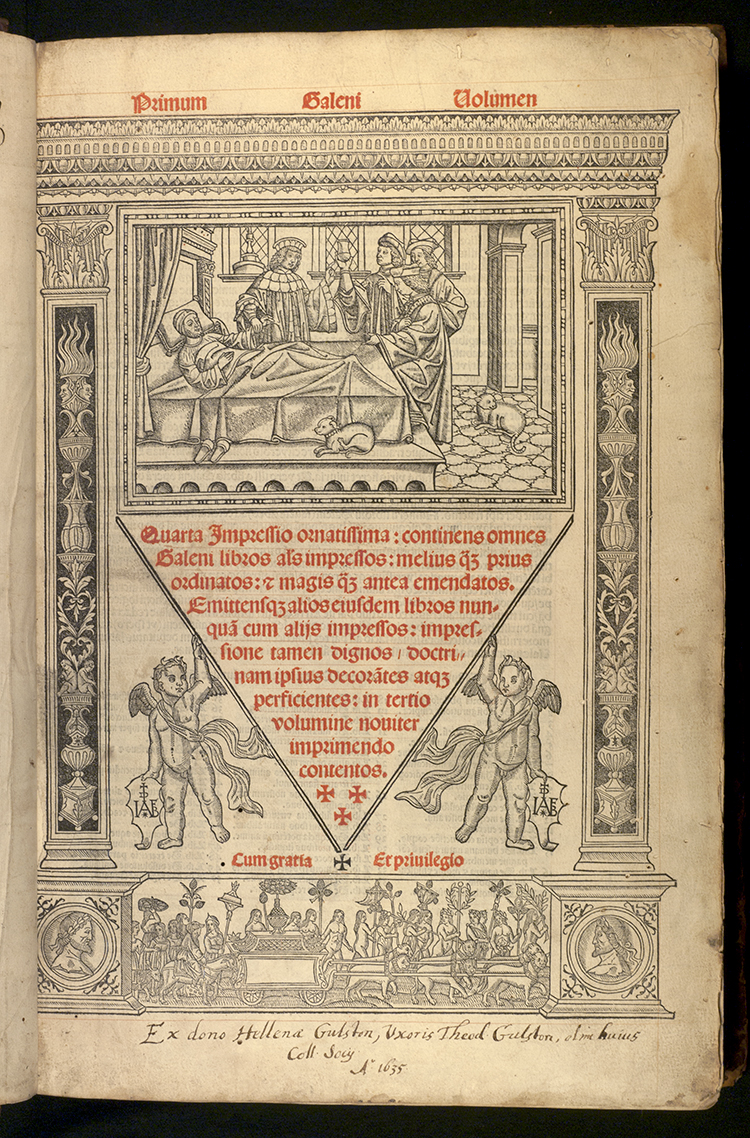

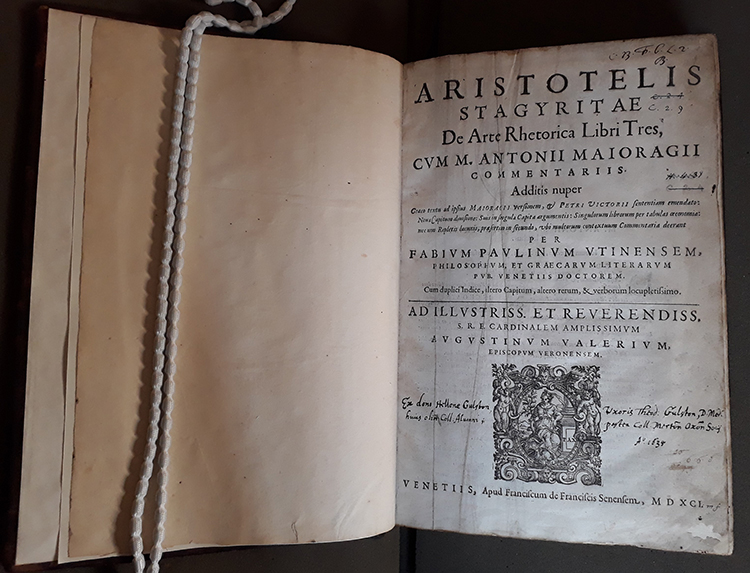

Some of the finest early medical books in the Merton Library have an inscription on the title page recording that they were the gift in 1635 of Helen Goulston, the wife of former fellow, Theodore Goulston. Goulston had studied first at Peterhouse in Cambridge, then transferred to Merton, where he took his MA in 1600 and was later elected junior Linacre Lecturer in Medicine in 1604. He left Oxford to pursue a career in London, and it must have been there that he met his wife. Helen was the daughter of George Sotherton, a prominent businessman in the City of London who served also as a member of parliament.

Photography by Colin Dunn (Scriptura Ltd.)

In London Theodore became an active member of the College of Physicians, and his medical practice flourished, no doubt benefitting from the many City connections of Helena’s family.

When Theodore died in 1632, Helen was sole executor of his will. She ensured that his memory was kept alive in his two colleges by overseeing gifts of books from his library to Peterhouse and to Merton. Although she may have been carrying out Theodore’s wishes concerning his books, the distinctive donation inscriptions in each of the Goulston volumes names Helen as the donor, and she thus has a continuing presence in the library. Helen died in 1637.

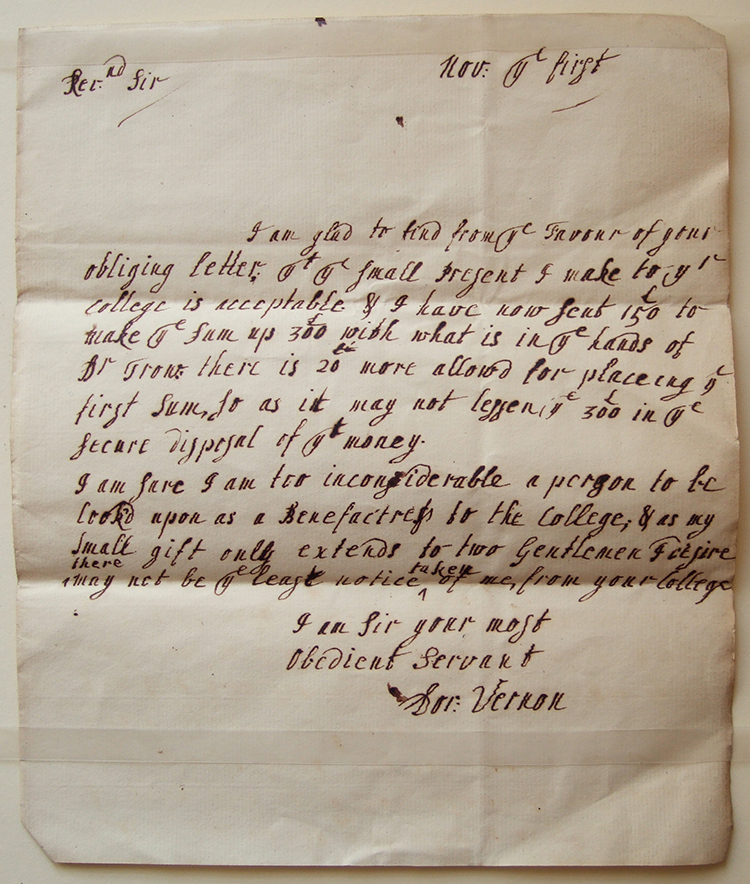

Few women have been in a position to match the benefaction of the Countess of Warwick in the late 13th century. More typical is the gift of Dorothy Vernon of Bourton-on-the-Water, Gloucestershire, who in 1754 gave the College £300 with which to purchase property, the annual income from which was to be used to augment the value of two of the Postmasterships (the Merton term for an endowed undergraduate scholarship). She added a further £20 to defray costs, so that the original sum would not be diminished in the execution of her plans.

Photo: © Copyright Steve Daniels and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Dorothy Vernon was the daughter of the Revd George Vernon (1637-1720), who had taken his BA from Brasenose College in 1657, and served as rector of St. Lawrence’s church, Bourton-on-the-Water, from 1667 until his death. He had acquired the patronage – that is, the right to appoint the minister – of the parish, to which he was succeeded by his elder son Richard, rector 1720-52. Little is known of Dorothy herself, except that she outlived both her parents and two brothers; a second brother Charles, also a clergyman, had died in 1736.

It is not known for certain why Dorothy Vernon chose Merton as the object of her charity, although it is just possible that there was a distant family connection through a Vernon who had graduated from Merton a few years earlier. Upon the death of her brother Richard in 1752, Dorothy had inherited the patronage of Bourton and had chosen as the next minister the Revd William Vernon. He is not known to have been a member of her immediate family, but was one of the Vernons of Hanbury, Worcestershire. It seems too much of a coincidence, however, for her chosen candidate to have shared her surname and that of the two previous rectors, especially when he in turn was succeeded by his own son, Edward Vernon. In 1764, while he continued to hold the benefice of Bourton, William Vernon was also appointed rector of Hanbury, upon the death of his cousin Thomas Vernon. This Thomas Vernon had matriculated from Merton in 1741 and graduated in 1746. If Dorothy Vernon was a relation of the Revd William Vernon then she would have stood in the same relationship to his cousin Thomas.

Dorothy Vernon followed her gift with a letter to the Warden, Henry Barton (Warden 1759-90), expressing her pleasure that “the small present I make to yr College is acceptable”, and which she concluded:

I am sure I am too inconsiderable a person to be look’d upon as a Benefactress to the College, & as my small gift only extends to two Gentlemen I desire there may not be ye least notice taken of me, from your College.