Ela, Countess of Warwick

Ela, Countess of Warwick, was the College’s first great female benefactor. As a contemporary of the Founder, her life illuminates the early history of the College. It also shows us the varieties of influence open to some aristocratic women in the age of Walter de Merton.

Ela’s ancestry was royal. Her father, William Longespée or Longsword, was an illegitimate son of King Henry II by a noble mistress, Ida de Tosny. One half-brother, Richard the Lionheart, arranged his marriage to Ela Fitzpatrick, heiress to the earl of Salisbury, and another, King John, enjoyed his company, appointed him to military commands and granted him rewards. He was a close friend of the knightly hero William the Marshal and worked with him to provide stable government in the minority of Henry III.

William was also an enthusiastic patron of the church, laying with his countess the foundation stone of the Lady Chapel of Salisbury Cathedral and endowing several monasteries and hospitals. No wonder the chronicler Matthew Paris called him ‘the flower of earls’. After his death in 1226, his widow, Ela’s mother after whom she was presumably named, founded a nunnery at Lacock in Wiltshire, became a nun and ruled it as abbess, dying in 1261. Of their four sons, two became clerics, one of them rising to the bishopric of Salisbury and supporting students at Oxford in the 1290s, while Ela and her three sisters made aristocratic marriages.

Ela’s first husband was Thomas de Newburgh, earl of Warwick. He was not a great figure in national or even, it seems, local politics, but on his death without children in 1242 Ela kept one-third of his lands as her dower. A dozen years later she married Philip Basset, who stood much closer to the centre of power. He was the son of Alan Basset, a royal adviser and diplomat, and brother of Fulk Basset, a conscientious and politically active bishop of London. Philip was a versatile servant to King Henry III, soldier, councillor and judge. He was also close to the king’s younger brother, Richard, earl of Cornwall, commemorated as a donor to Merton as Richard, King of the Romans.

In the dramatic struggle between Henry III and Simon de Montfort, the conflict through which Walter’s plans for the College took shape, Basset was a ‘moderate royalist’ (as Malcolm Hogg put it), a natural ally for Walter. Between 1261 and 1263 Walter and Philip between them led the king’s administration as chancellor and justiciar. In 1262 Philip was one of the witnesses when Walter entrusted the lands that he had been buying from the profits of his career in royal service to Merton Priory in preparation for the establishment of his scheme to fund scholars at Oxford. In November 1266, two years after the College’s first statutes had been issued, Philip and Ela made a major donation to Walter’s project. They granted the manor of Thorncroft in Leatherhead, Surrey, to Walter for his life and his ‘house of scholars of Merton’ after his death. In 1268 he handed it over to the College and it still remains in our hands.

Philip Basset’s death in 1271 left Ela with yet more dower land and, as she did not marry again, considerable freedom of action. She followed the example of her mother and father in generous patronage of a variety of religious institutions. Some of these donations were to old-established Benedictine or Augustinian houses, others to newer initiatives like the London house of the Franciscans, to whom she gave two blocks of property in the unpleasant-sounding Stinking Lane.

Some of Ela’s benefactions met the conventional obligations of family connections and local lordship. She gave lands to St Sepulchre’s Priory, Warwick, for example, to pray for the souls of her late husband the earl of Warwick, her mother, father and siblings. Others were more idiosyncratic. She seems to have had a particular concern that those she favoured should eat and drink well, perhaps fitting given the role of great ladies in supervising the hospitable life of the great household that was such an important instrument of social and political power in her world. Her grant to Reading Abbey in 1282 provided for a special distribution of spices to the monks and extra food on Thursdays and Sundays.

Like her mother she decided to spend her later years in a religious house, though as a vowess, pledged to chastity, but not fully a nun. Ela chose Godstow Abbey, on the far side of Port Meadow from Oxford. It had royal connections. Kings Henry I and Stephen had been involved in its foundation and her grandfather Henry II was very generous to the house, apparently because another of his mistresses, Fair Rosamund de Clifford, was buried there. Its nuns were often from aristocratic families, so Ela probably felt at home in their company. But another attraction must have been its proximity to the College and the University, with which she was enthusiastically engaged.

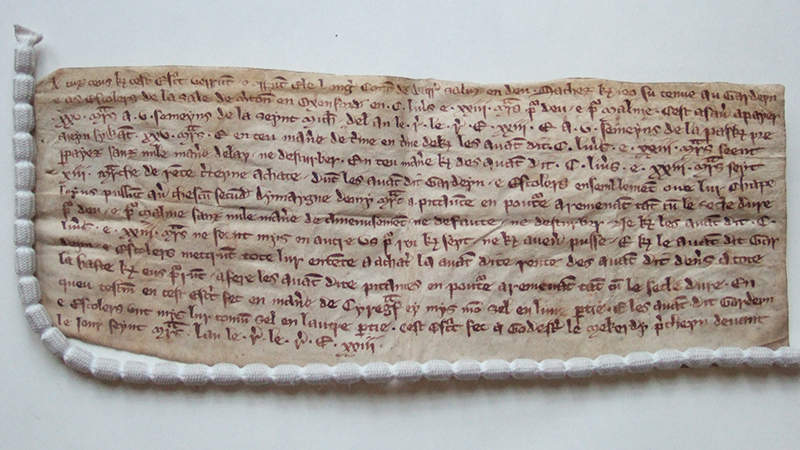

She gave money to Balliol for the building of its chapel and on a broader scale established the Warwick chest, a fund from which the University could make loans to poor students. But her links with Merton were particularly warm. The Warden and Fellows tipped her servants as they worked on her room in the nunnery, sent her gifts of goat kids, ginger, and other foodstuffs and several times even dispatched boats to Godstow in connection with her business. She wrote heartfelt letters to the Warden in French, rather than the Latin used by the scholars, addressing him as her dear special father in God, asking for his help and advice and pledging that making gifts to the College was one of the things she most desired on earth. The letters also show her to be well on top of the necessary business dealings, detailing the terms of leases on her dower lands which would enable her to make the gifts she had promised and even making provision to make up the difference if her farm profits were cut by royal taxation.

Ela died on 12 February 1298 at what must have been an advanced age. The Warden and Fellows made an offering at her funeral, gave a large gift to the bishop of Salisbury, her brother’s successor, who also attended, and sent gifts of food to her executors, among whom the Warden served, as they sorted out her affairs. From then on, the Fellows must have remembered her every second Sunday, as they enjoyed the drinks that she had endowed for them, and especially on St Matthias’ day, 24 February, as they prayed for her soul and enjoyed the additional drinks that she had provided in another of her benefactions. We too can raise a glass to her memory, as a shield of her arms with its six lions has been fixed on the wall of the Hall for more than a hundred years.

Steven Gunn, Fellow and Tutor in History