Merton in… the response to Covid-19

The Merton community has been involved in many ways in reacting to the coronavirus pandemic: on the frontline as medics, as researchers into the virus, as carers for the vulnerable in the community, and as stalwarts who keep the business of the College running and its members connected.

Postmaster spoke to a selection of alumni, Fellows, current undergraduates, graduates and College staff to gain a small insight into this collective response. Please bear in mind that the interviews were conducted in July 2020, and some statements may now be out-of-date – though the sentiments of help and cooperation remain unchanged.

Ruth Taylor (1984) is a GP and senior partner at a general practice in Worcester. Although she says that she had no fear for herself when the outbreak began, she did check that her children knew where her will was. “My members of staff were really quite frightened – there was a feeling that we would be overwhelmed.”

In common with many general practices, in the initial weeks routine work was cleared and there were many changes in the ways of working, not least a huge uptake in remote working. “We were worried about doing palliative care remotely, worried that we would run out of syringe drivers, and we had to devise improvisation plans. We were outside our comfort zone, but people did follow the government guidance to stay at home and reduce the pressure on the NHS, so we weren’t overwhelmed and we did manage to look after everyone.”

Ruth is now concerned about the collateral damage in the community: cancer patients who have not been seen; mental health issues coming to the fore; domestic violence, abuse, suicide attempts and alcohol problems.

“When I trained to be a doctor, I never thought I would be risking my life. Now I really feel I have done something useful, and feel part of something much bigger. Now we’re trying to get back to normal work while keeping socially distanced from our patients. And that’s not easy.”

Many alumni have been involved in research. Marc Lipsitch (1992) is Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and Director of Harvard’s Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics. His main line of research studies the effects of treatments and vaccines on pathogen populations, and the consequences for human health.

He states:

“At the start, I had a feeling of dread. We had had dress rehearsals with SARS and H1N1, but this was different. After the first few weeks, the scale of the pandemic became clear so we increased our research involvement, collaborating widely with others in the same field.”

Marc’s own research involves the immune system, determining how you can tell whether people are protected by previous exposure. He also researches how to allocate vaccines to maximally reduce transmission.

At the start of the pandemic, he sought to understand the seasonality of coronaviruses in general, and to assess the consequences if SARS-CoV-2 followed a similar pattern. Other early work involved investigating groups of travellers with Covid-19, trying to extrapolate the data to discover patterns in the source population.

His current research efforts focus on serologic data analysis. “But it’s going to be a long haul, as natural immunity and perhaps even vaccine-induced immunity may be partial and not last forever.”

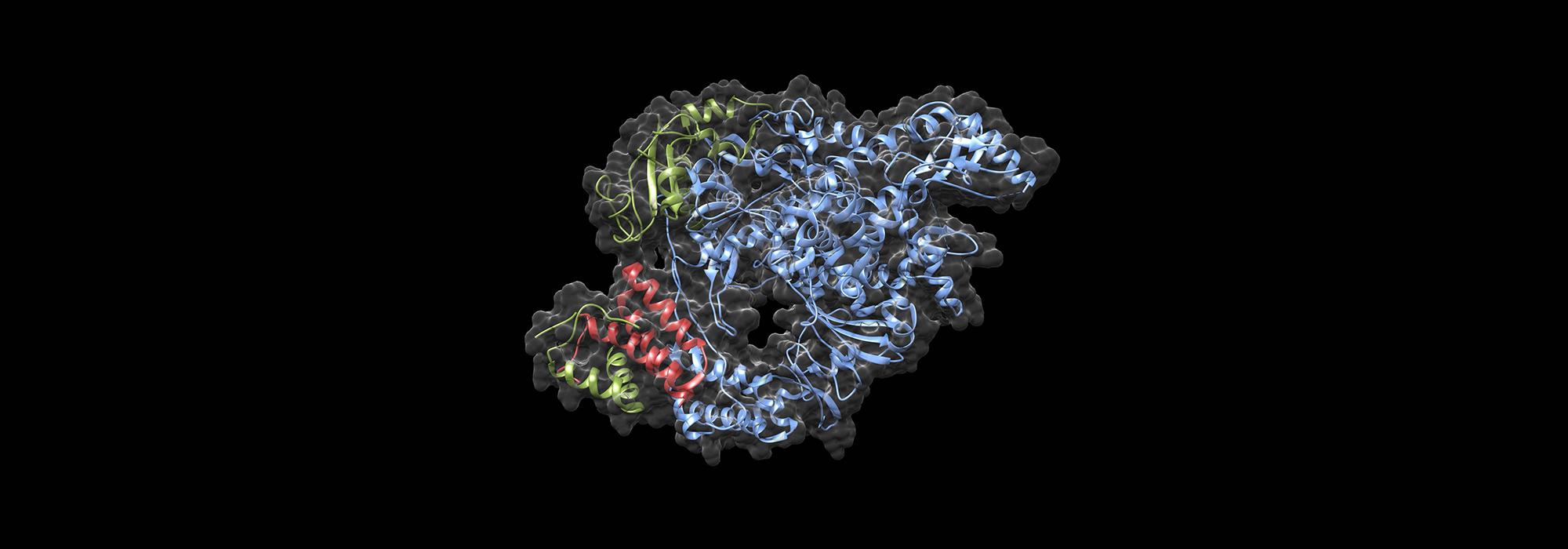

In the UK, Dr Christopher Cooper (1994), Senior Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Huddersfield, is working on computational analysis of the structure of some of the proteins in SARS-CoV-2.

Knowing the shape of the protein can help with drug design, and Chris’s group is using computational structural methods to find new targets to help develop the chemistry, so that novel drugs can be developed. Some of the proteins in the Covid-19 virus have already had their structure determined from similar coronaviruses: SARS and MERS and also coronaviruses that cause some common colds.

Chris’s group is trying to predict the structure of the other proteins, and model compounds that bind to them to find out if they can act as potential targets for drug inhibition. The viral helicase and RNA polymerase are some of the important proteins, as they unwind and copy the viral genome during its replication cycle.

Chris says modestly:

“Mine is very small-scale research, but it is all part of trying to understand the disease – to find out how the virus works. Every bit of knowledge helps. You try and do your bit. If future related pandemic viruses develop, then we hope to have additional lines of attack.”

At the community level, Sara Fernandez (2006) worked with Oxford City Council to set up Oxford Together in partnership with Oxford Hub, the volunteering charity of which she is CEO. “I’m Spanish and my mum is a nurse in Madrid, so I was fearful about what was going to happen here.”

Sara’s team went into action on 12 March, devising a response plan. The first step was to divide the city into 600 segments. About 5,600 people signed up as volunteers, of whom more than 2,000 were matched with tasks. Street Champions were allocated as the first point of contact for help with local shopping and collecting prescriptions; other volunteers manned the phone lines, either receiving calls for assistance or making regular calls to lonely people. In partnership with a charity in Didcot, Oxford Together arranged the delivery of 1,600 food parcels a week. Volunteer mechanics repaired abandoned student bikes to give them to key workers so that they could avoid public transport. And many students gave online tutoring classes for secondary school pupils.

“Oxford City Council couldn’t have matched the level of need if our volunteers hadn’t stepped in. We’ve been around as a charity since 2008, but our work has been more appreciated and more visible because of the Covid crisis.”

And if we didn’t know anyone personally who had had coronavirus severely enough to be admitted to hospital, Dominic Minghella (1986) put us in the picture through his articles in the Telegraph and Observer. Fortunately, he has recovered completely, with no lasting ill-effects. However, his was a harrowing experience at the time; he even penned farewells to his family. He wrote about not only his symptoms but also the frightening ordeal of being in hospital, surrounded by people whose faces he could not see.

Dominic says he wrote the piece “because I felt traumatised by the experience, and it felt like a way to exorcise it. I also felt that, in the early phase, a lot of people wanted to know what having the virus was really like.”

Even though Dominic was fit enough to travel to Italy as usual this summer, his body appears to have flashbacks. “Packing for Italy, I opened the same travel bag that I had taken with me to hospital, and my hand and my whole arm started shaking. My body hasn’t forgotten about it.”

Dominic also wanted to join the debate about what was being done and not done, and the divisions caused. “I’m sad about that because we are all vulnerable together and we all need to get out of this situation together.” He wrote another article, in the New Statesman, about the 11 days of March, from 12 March, when contact tracing stopped, until lockdown was imposed on 23 March, “because so many people were hungry to know about that. I’ll leave it to others now.”

Hilary term 2020 managed to come to an end as scheduled, on Saturday 14 March. But within just over a week, Monday 23 March, the government announced a lockdown. Many students had already left Merton for the vacation, but many foreign students – mainly graduates – remained in College. The College remained closed throughout Trinity term.

Lucy Buxton (2018), as JCR President, had the task of holding the student body together during this time.

“The biggest challenge was that we weren’t able to do anything in person. Previously we did very little online – it was all in person, especially in Trinity term: garden parties, barbecues, sports days. So we had to have quite a bit of a rethink, shifting everything online and keeping people engaged, even though we were all dispersed.

“Our job was to keep morale up. We set up a Facebook page called the JCR Isolation Station, and set a corona challenge every week – for instance, photography or baking. We introduced an ‘Adopt a Finalist’ scheme, whereby volunteers in the younger years sent care packages and a little note to finalists.

“I’m proud of the way the JCR has adapted. Just handling everything and being stripped of all the fun that Oxford has to offer. We managed to stay in touch and still be quite chipper. That was quite an achievement.”

MCR President Lucas Didrik Haugeberg (2019) had a similar cohesive role to play.

“The MCR’s job is to represent the students to the College and also to be responsible for the social activities. Representing the students to the College was as normal and worked well online. But Merton’s MCR is one of the most active in Oxford. We organised some online social events, but it’s not the same as having the collegiate experience.”

The Big Merton 1264 Challenge was the highlight of the online Trinity term – an initiative devised by the Warden, Lucy and Lucas. The aim was not only to bring the Merton community together, but also to raise money for a hardship fund to provide support to all members of the College who are in need. Students, staff and alumni were encouraged to create their own challenges based on the number 1264 – Merton’s foundation year. The Warden kicked off the Challenge by running 12.64 km with her husband and daughter; others baked cakes, did press-ups, concocted photo collages, several wrote short stories in 1,264 words.

Now things seem as if they will be going back to quasi-normal. Says Lucas:

“It’s going to be nice to be back. Now we are organising the MCR Freshers’ Week. The College has been very supportive. I think we will be able to produce a memorable event.”

DPhil student Alexandra Fergen (2017) set up a practical initiative in Oxford: the Bridge of Charity – a local initiative based on the German Gabenzäune (donation fences), where locals can leave a bag on a fence for anyone in need to take.

“I’d read about these in Germany and I’d also read articles on food poverty here.”

After speaking with the Lord Mayor who welcomed her initiative, Alexandra made a banner, hung it over the pedestrian bridge outside Oxford railway station, and publicised it on social media. People who wish to donate simply put a few basic necessities in a bag and tie it to the bridge, for someone in need to take. Items have to be long-lasting and packaged, such as tins of food or toiletries.

It was so successful that Alexandra started another Bridge of Charity on Donnington Bridge, which has seen even more use.

“The response has been absolutely heart-warming. I go there and check regularly, so I know it’s used. People are still in need. I believe that we all have a responsibility to care for one another, and this is one way to show it.”

The medical students, of course, have been either very close to the front line or on the verge of joining it. All the final-year medics were accelerated into junior doctors, starting four or five months earlier than usual. Clinical students from the earlier years, who don’t yet have the training, have helped in other capacities. For instance, two fourth-year medics, Joshua Navarajasegaran and Adam Carter (both 2016), have been working as volunteers in the John Radcliffe Hospital (JR).

Josh reports:

“Our medical studies were put on pause in the middle of March. I was in the middle of a surgical rotation when we stopped. Adam and I were given the opportunity to volunteer with the Oxford University Hospitals trust. For three months from April till June, I was working Monday to Friday at the JR hospital pharmacy. I was providing general support but mainly delivering medications to all the wards all around the hospital including Covid wards, clocking up about 15km around the hospital every day.

“It’s been great to be given the opportunity to help out during this time and feel part of the team in the pharmacy. Thankfully, on 6 July, we restarted our medical course.”

Many of Merton’s Fellows and doctoral students have been involved in research into different aspects of the virus and its effects. Professor Julian Knight, Tutor in Medicine, has been working to understand why some people develop severe disease whereas others are affected only mildly or are asymptomatic. He is the Chief Investigator for a collaborative research project of about 100 researchers in Oxford who have joined forces to conduct deep phenotyping of patients with Covid-19, to try and identify the phenotypes of those who are most at risk.

Julian explains:

“We have recruited a core set of about 140 Covid-19 patients in the John Radcliffe and taken blood samples to try and understand their immune response, by the differences in the proteins and RNA molecules in individual cells.”

This information is enabling generation of the Covid-19 Multiomics Blood ATlas (the COMBAT project).

Single-cell RNA sequencing is very expensive, and so cannot be done on a large scale. This research effort will be one of the biggest single-cell investigations ever, involving more than 60 billion individual sequencing reads.

The group has already generated data and is now starting to see the biology, with different immune cell responses in different patients. Although there are no definite answers yet, Julian can see a time when they will be able to classify response to Covid-19 using molecular signatures rather than rely on assumptions.

Sunetra Gupta, Professor of Theoretical Epidemiology, has been in the media frequently during the coronavirus pandemic, for her modelling predictions. Unlike the large and complex models of the Imperial College group, which predicted a very large number of deaths, Sunetra’s model is much simpler, and gives qualitative insights but nonetheless translational information.

Sunetra says she usually steers clear of policy issues but feels she had to get involved this time:

“I’m very exercised about the effects of lockdown. I thought it was important to make the government aware that a simple model could equally well fit the same assumptions, and that the Imperial College predictions were an extreme worst-case scenario.

“To distinguish which model was more accurate, we needed a test to see how many people had been exposed to the virus. So we set about developing a test for antibodies that neutralise the virus. Unfortunately, the tests vary in sensitivity, and it turns out that not everyone makes antibodies. So our focus has shifted to trying to get a fuller picture of who has already had coronavirus and who has protection.”

Sunetra has been particularly vocal about lockdown, and the need to consider the overall welfare of the country. As she puts it:

“The epidemic is not independent of us; it depends on what action we take. The data shows very clearly that mortality is confined to a vulnerable fraction. The real questions are: who is vulnerable, and how can we protect them?”

Professor Irene Tracey has also been concerned about the effects of lockdown and possible viral infection in the brain. With international colleagues, the Academy of Medical Sciences and the mental health charity MQ, she co-authored a position paper that highlighted the potential neurological and mental health impact of infection. The article was fast-tracked and published in The Lancet Psychiatry online in April, with the print version in June.

After the initial focus on respiratory problems, countries ahead of the UK in the pandemic were starting to observe neurological problems in Covid-19 patients. There was a growing realisation that the virus effects on the brain and the effects of lockdown would impact people from a mental health as well as a neurological perspective, which the group was keen to flag.

Says Irene:

“We wanted to highlight this issue and to make sure we got brains and samples quickly enough for research purposes so that we could direct resources and learn. The point of the paper was a call to arms, to ensure that the effects on the brain were not ignored, and that the consequences and risks of isolation for those suffering with mental health issues, obsessive compulsive disorders, addiction and other risk factors were flagged.”

Testing is a major part of the response to the Covid-19 pandemic. But many governments and local administrations are struggling to meet the capacities needed for their testing strategy. A group involving three Merton DPhil students – Divya Sridhar (Zoology), Edwin Lock (Computer Science) and Jakob Jonnerby (Physics) (all 2016), with Bodley Fellow Professor Christopher Ramsey in an advisory position – have turned the problem of testing constraints on its head. They have devised a novel testing and containment strategy that involves group testing and makes the most of existing capacity. It requires many fewer tests while diagnosing as many infected people as possible. The mechanism can also be used proactively to monitor smaller populations such as schools, universities, hospitals or refugee camps.

Edwin explains:

“Our approach is to assume that an organisation has a certain number of tests per week, and then decide the best way to allocate those tests. Treating this as a resource allocation problem, we classify the population according to their exposure to others and to the virus, and also according to their cost of containment.”

This allows them to determine the best way of allocating available testing capacities to the different categories.

In her research on the epigenetic regulation of stem cells, Divya routinely uses a certain technique that is considered the ‘gold standard’ testing methodology for Covid-19. This experience means she is well placed to advise on the number of samples that can be pooled for group testing and how to scale up testing procedures.

The group have been in discussions with the NHS about streamlining the UK’s testing process and have requested permission and funding to carry out a pilot of their mechanism in Oxfordshire-based care homes. In July, they were awarded a grant to help apply their mechanism in disadvantaged communities in Mexico.

Tracking the response of governments to the Covid-19 crisis is another important piece of the jigsaw. Francesca Lovell-Read (2015) is a DPhil student at Oxford’s Mathematical Institute, doing mathematical epidemiological research. She was working on plant diseases when the coronavirus pandemic took off, but is now engaged with University-wide research, initiated by the Blavatnik School of Government, to develop a tool that tracks the response of governments to the pandemic.

The Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker takes into consideration many different interventionist measures such as school closures, workplace closures, travel restrictions and fiscal stimuli. Francesca is involved in data collection for the tracker, which now has data from more than 160 countries. The different indicators are scored and collated to indicate the number and strictness of the policies.

Francesca emphasises that “this is not a score of how well a country is doing but is more of a comparative measure of the strictness of approach of different countries”. This is a massive tool, with the results publicly available to inform action and advice issued by governments and bodies such as the World Health Organisation.

Progress on a vaccine against Covid-19 is moving fast. At the time of writing, in late July, it appears that the coronavirus vaccine developed by the University of Oxford is safe and triggers an immune response. The trials involved 1,077 people, among whom was Emily Bruce, Merton’s new Alumni Communications Officer.

Emily volunteered to help with the coronavirus trials because, as she says, “I felt I should do something – make some small contribution to the fight against the virus.” She passed the screening test and was given the vaccine in early May. In fact, half of the people in the trial were given the trial vaccine, and the others were given a control vaccine, but neither the participants nor those administering the injection knew who was receiving which.

For a month afterwards, Emily had to complete an electronic diary daily, to check for any reaction (there was none), and will have other check-ups after six months and a year. By the time that Postmaster is published, the reality of a vaccine may be even closer.

Many aspects of College life, of course, were greatly changed. With very few students in residence, the College had spare capacity, and was able to offer accommodation to three doctors at various times during lockdown, as they were working either at the JR hospital or with the homeless.

The College kitchens closed at lockdown, but not before Head Chef Mike Wender had packed up as much food as possible, either to vacuum pack for storage or to give away. Plates of food were delivered to the doors of the few self-isolating students in College, and a temporary ‘shop’ was set up in the College Bar, with the Head Porter acting as the shopkeeper. The kitchen staff were put on furlough for several months, though Mike was brought back much earlier to help with planning for the new arrangements.

New working practices include distance alarms, plastic screens and different procedures for meeting suppliers. Says Mike:

“The other big change is that the chefs will have to do their own cleaning now.”

Whereas the kitchens look after the body of the College residents, the Chaplain, the Revd Canon Dr Simon Jones, and his team look after the soul of the student body. At the end of Hilary term, all but about 15 undergraduates had gone home, though about 80 graduate students remained.

“Early on, a few people were self-isolating, so the welfare team checked in on them each day and made sure they had what they needed. Then we set up online resources: things that we would normally have done in person, we moved online, such as yoga and other activities.”

Chapel services continued throughout lockdown, but online. It was fortuitous that webcasting equipment was installed in the Chapel last year, so the College already had a wealth of recorded music from the College Choir and the Girl Choristers. During Holy Week, a movement from the College Choir’s recording of Gabriel Jackson’s The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ provided a focus for each day’s reflection.

Once term started, there was Zoom Morning Prayer every weekday and a pre-recorded Sunday evening service on YouTube, with Zoom drinks afterwards. “We had up to two screens’ worth of people (that’s about 40 people) each week and being online meant that some alumni were able to join us.” The Sunday evening virtual drinks also provided the setting for the farewell to the outgoing Associate Chaplain, Jarred Mercer; a welcome to his successor, Melanie Marshall; and farewell drinks after the Leavers’ service.

The last word in this article goes to Irene Tracey, wearing her hat as Warden rather than as neuroscientist.

She understates the case when saying:

“It’s been quite the first year! There’s always something that challenges you early in a new job, but I was not expecting a global pandemic. What's been really impressive is how well everyone has come together: staff, Fellows and students.

“We pulled it off as an institution at both a college and university level with everyone working collaboratively. Staff have been adapting to changing circumstances; tutors have worked without a break, sacrificing their Easter vacations to prepare the next term’s courses and exams, all online. Creating an online degree course in two months’ flat is beyond impressive. The students have been incredible - tolerant, patient and forgiving. Whether first years or finalists, they rose to the challenge and just got on with it.

“We feel rightly very proud of how well Merton’s community has responded to the pressure. It has showed me what an inspiring place this is and just how fortunate I am to be among such wonderful people.”

We are aware that many more within our community have been involved in the fight against Covid-19. Please contact us at publications@merton.ox.ac.uk to share your story.