Merton’s copy of Caxton’s first edition of Canterbury Tales

At the age of 50, William Caxton decided to turn away from his long and successful career as a merchant, and focus instead on the production of books. Having printed several in Bruges from around 1473, he moved his press to Westminster around 1476, introducing England to the technological revolution that had been sweeping across Europe since the 1450s. The first book off Caxton’s press had to be a commercial success, popular enough to recoup his huge investment in paper, fonts, and labour. But the demand for marketable Latin texts — religious and scholarly books — was already supplied by imports from the continent’s printers. There was a gap in the market, however, unfilled by continental imports: English vernacular literature. One poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, had proved himself to have an especially enduring appeal, attested by the many surviving manuscripts of his poetry created after his death in 1400 — an industry that was still thriving when Caxton decided to print his works. No wonder, then, that the first book Caxton printed in England — the first book ever to be printed in England — was this edition of the Canterbury Tales.

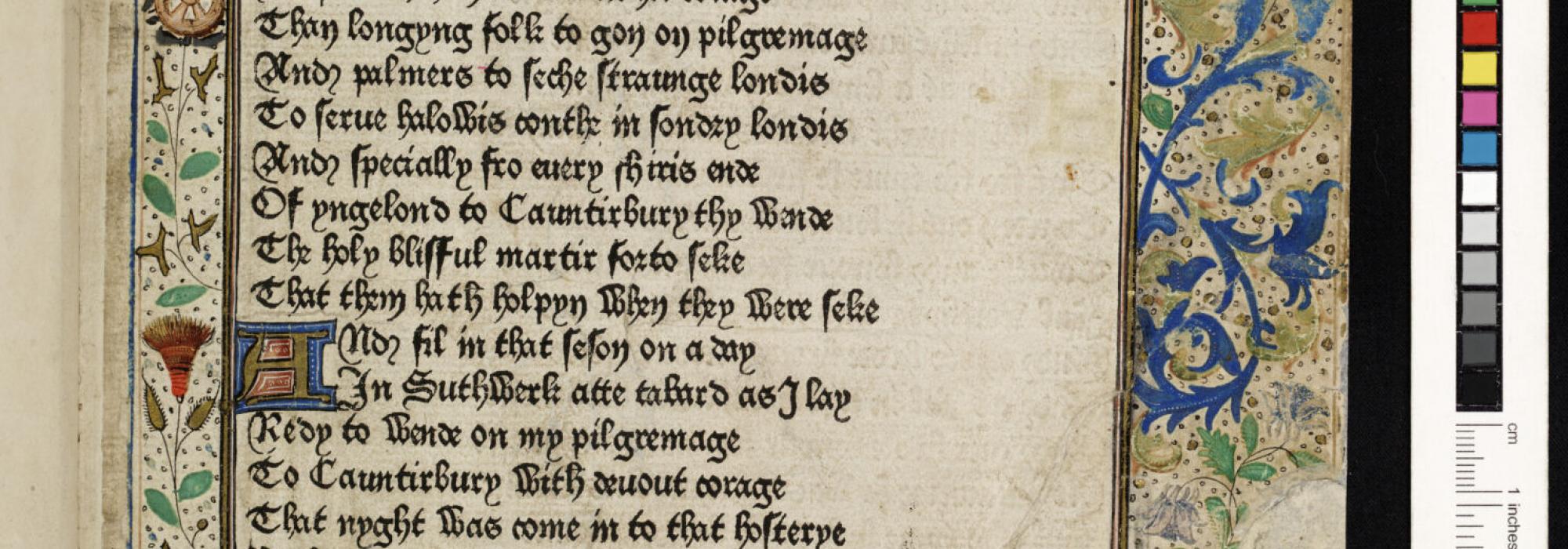

Around 21 copies of this milestone survive today, in various states of disintegration (only single leaves remain of many). Merton’s copy is not just remarkable among these for its completeness, but remarkable among all English printed books for being lavishly decorated by hand. It contains 21 leaves with elaborate floral borders, illuminated with gold, and decorative red and blue initial letters are hand-drawn in throughout. The first border contains a clue to the book’s first owner: the arms of the Haberdasher’s company show that this book was commissioned not for royalty or aristocracy, but for a merchant. The motifs found on the arms, a brush and a millwheel, recur throughout the book, nestled in the foliage of the borders.

Augmenting printed books to this degree was an extremely rare practice, illumination and bordering usually being reserved for manuscripts. A.S.G. Edwards counts only 8 other Caxtons that contain gold decoration of any sort, and none as elaborate as the Merton Caxton. A later artist admired the skill of these borders, using them as a model for another book: on at least two leaves, the outlines of the floral patterns have been perforated, tiny holes pierced through the page (fol. 67, fol. 77). This is evidence of a technique called pouncing, used to transfer the design to another piece of paper. Chalk, or a similar substance, would have been forced through these holes to reproduce the outlines on a blank piece of paper held behind it, allowing the artist to then go over them with ink.

This book, then, lies at the meeting point between the two technologies of manuscript and print. Caxton’s printing endeavours did not exist in a vacuum, and he would have joined an industrious network of scribes, illuminators, rubricators, and bookbinders. While illumination is rare in fifteenth-century printed books, less elaborate signs of manuscript influence are typical: they are often ‘rubricated’, for instance, meaning that text and decoration were added in red ink by hand. Early typeface designs also took their cue from manuscript production, with this one (Caxton’s Type 2), modelled on the scripts of Flemish scribes. A close look at the pages reveals another hybrid feature: faint red lines surround and underline the text on most pages, as if providing guidelines to keep the writing straight. But this text isn’t written, it’s printed, and these ‘guidelines’ were in fact added after the impression was made. What was once a functional feature, a method of production, has here become decorative, added to make the book look more like its manuscript precursors. Designs that imitate functional features for decorative ends are known as skeuomorphs, and such creative skeuomorphism characterises these early years of typography.

Caxton’s personal admiration for Chaucer is evident in his many prefaces and introductions to the books he chose to print. Chaucer was the ‘worshipful fader [i.e. father] and first foundeur and enbelissher of ornate eloquence in our Englissh.’ (De consolatione philosophiae, 1478). Caxton praised Chaucer’s ‘crafty and sugred eloquence,’ and ‘hye and quycke sentence’ (Canterbury Tales, 1483; The book of fame, 1483). For all this appreciation, it’s curious that this first edition of the Canterbury Tales contains no preface: here, Chaucer needs no introduction. Caxton does, however, mention this book in the preface of his next edition of the Tales, printed in 1483. Some time after the first was printed, he explains, a ‘gentylman’ approached Caxton, observing that the book contained errors, ‘and said that this book was not according in many place unto the book that Geoffrey Chaucer had made.’ The man lent Caxton a manuscript that was ‘very true and according unto his own first book,’ and it was from this that his second edition was printed. We might speculate whether Caxton’s newly corrected edition was just a ploy to sell new Chaucer to old customers. Certainly, though, the errors of the first were intolerable to a previous owner of the Merton Caxton: corrections have been made throughout in a fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century hand, usually taking the form of missing words or entire lines added in the margins. Occasionally, the word ‘vacat’ (Latin for ‘it is empty’) is written around a line, indicating that something is missing from the text (e.g. fol. 139r).

These corrections are the earliest of many attempts to fix the book’s perceived deficiencies over the course of its life. Several pages have rips in their lower edges (the consequence of fervent page turning?), and though conservators have since skilfully repaired them, they were once patched up with paper. We see evidence for this in the rectangles of discolouration that halo many of the tears — stains from the adhesive used to paste in the patches (see, for instance, fols. 230v, 324v). More drastically, in the nineteenth century the book was found to be missing three leaves. These have since been replaced, transplanted from two other books — a practice known in its own time as sophisticating a book. Alongside the original pages, these additions are clearly of another source: their text is underlined in a way not seen elsewhere in the book, and their rubrication is by a different hand (fols. 169, 176, and 188). The last of the three has a credit to its donor: ‘this leaf was given to Merton College Library by Earl Spenser 1815’. The remaining two were bought for £21 in 1820. We can see that at least one of the missing pages had an illuminated border, as the page after its replacement is stained by the blue ink transferred from its former neighbour (fol. 169r). This probably explains its disappearance—removed deliberately by a covetous reader or collector.

Before these pages were inserted, the book had been bound in the wrong order. A hand-written note on fol. 241v attempted to guide the reader through the textual labyrinth: ‘go to the paper marked * ‘. The acquisition of replacement leaves in 1820 presented an opportunity to untangle the text — the book would have had to be completely unbound to add them, and could have been rebound in the correct sequence. But, while some order was restored, new binding errors were introduced elsewhere, producing a text that jumps confusingly from tale to tale.

The book is thought to have been given to the college in the period 1620 to 1630 by William Wright (c.1561–1635), who was a goldsmith, a baker, and then Mayor of Oxford in 1614. He left no mark of ownership on his book, unlike a previous owner, Humfray Cole, who wrote his name in an italic script on fol. 197v. The Merton Caxton is a complex object that has accrued such marks of use since it came off the press in 1476. These decorations, holes, edits, rips, stains, repairs, and inscriptions are each a trace of the craftspeople, editors, merchants, scholars, conservators, collectors, binders, and readers through whose hands the book has passed over its long life.

Dr James Misson

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Photography by Colin Dunn (Scriptura Ltd)

Edwards, A.S.G., ‘Decorated Caxtons’, in Incunabula: Studies in Fifteenth-Century Printed Books Presented to Lotte Hellinga, ed. Martin Davies (London: British Library, 1999), 493–506

Gillespie, Alexandra. Print Culture and the Medieval Author: Chaucer, Lydgate, and Their Books, 1473-1557. (Oxford: OUP, 2006)

Hellinga, Lotte, William Caxton and Early Printing in England (London: British Library, 2010)